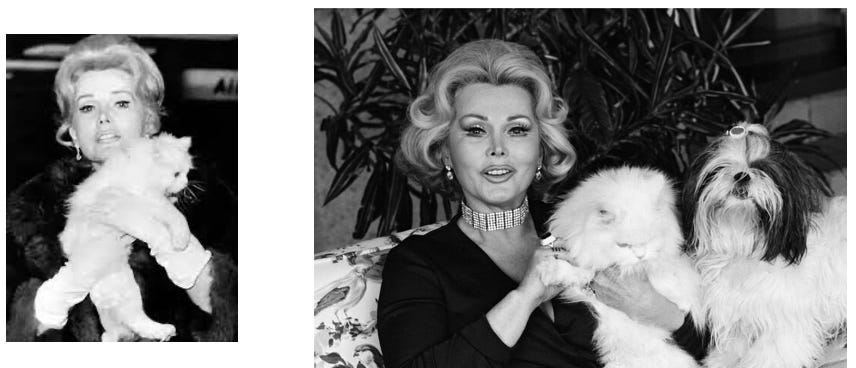

I would sacrifice every diamond I own or ever have owned for the life of one of my animals. — Zsa Zsa Gabor

Today’s poem, “Is Spot in Heaven?”, may seem oddly elliptical on first reading. Not to worry. I’ve mapped it below…dare I say better than Google AI could do? It’s an excellent poem, worth spending time with.

I confess that the first couple of times I read the poem I wasn’t sure what to say. Then I realized that it functions, structurally, like a traffic roundabout: it’s circular with changing angles and moods and finally, to mix a metaphor, it takes off like an enormous aircraft or space ship headed to a happy realm.

Yes, reading this poem is like entering a busy roundabout in your car. Traffic flows in one direction around a central island, with priority given to those vehicles already circulating. Let’s put Spot on the central island and join the circular caravan that swirls around him.

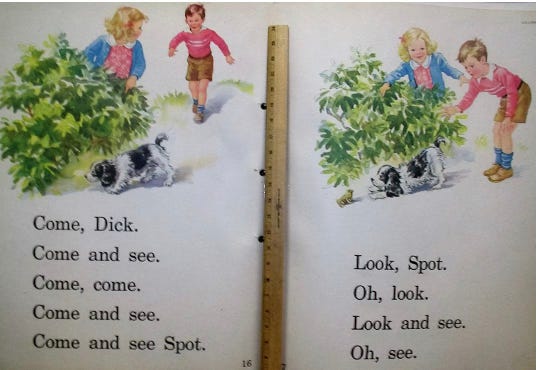

The title prepares us for a poem about a dog, but we don’t immediately encounter Spot. Already rotating in the poem, like a heavy truck in the roundabout, is a conversation taking place in Russia — St. Petersburg, formerly Leningrad — between Sasha, a tourist guide in the zoo, and the speaker, who is presumably American. Why do I presume he’s an American? Because Spot used to be a typical dog’s name in this country, especially if the dog’s owner was old enough to recall those Dick and Jane readers in first grade. Their dog was Spot, their cat was Puff.

Sasha supplies the useless information that “they,” meaning Russian officialdom in all its lethargy, are “restorating” — he means “restoring” — a zoo compartment that will eventually house an elephant. “The building,” he says, “is not enough big.” We hear his accent in his mispronunciation and in his reversal of the adverb “enough” and the adjective “big.”

The American speaker’s skeptical question — “Where’s, um, the elephant?” — expresses his boredom on this tour. We can guess that the zoo is on the shabby side, like the guide and like so much in Russia. The elephant is “somewhere,” and Sasha couldn’t care less: “How should I know?”

Traffic has been slow and orderly so far. Then, Whoosh! Suddenly we’re in a fast lane and accelerating, we probably cut off another vehicle as we zipped in without a blinking signal. The speaker is suddenly back in childhood, six years old and reading about Spot in first grade and that’s of course the name he gives to his dog, a brindled terrier.

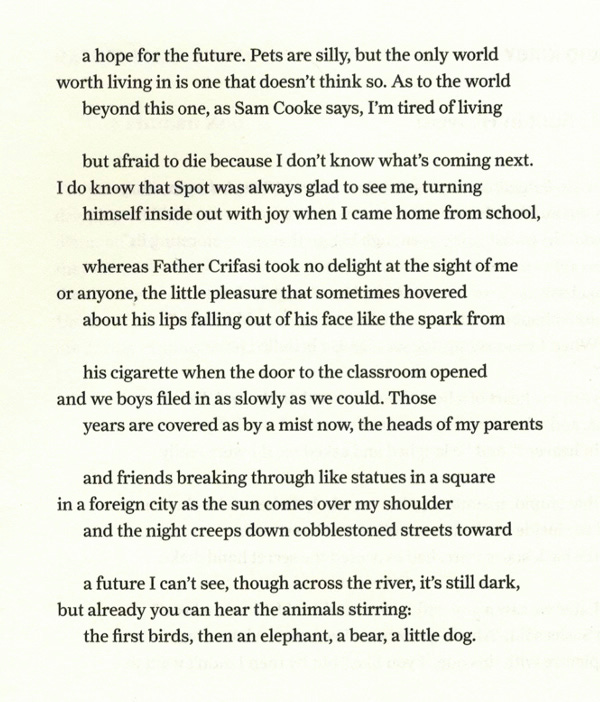

We’re over the speed limit, the speaker is disturbed by childhood memory as he races through Spot’s biography: a lionhearted, unstoppably energetic pet who lived his life and then died, as the speaker, now much older, reflects that all of us, like Spot and like every living thing, must die. For that reason, religions were invented to provide hope for an afterlife.

The speaker recalls his question to the priest of his church, Father Crifasi. He asked the natural question of a child who has lost a beloved pet: “Is Spot in heaven?” Instead of a sensitive answer such as, “I think there’s a very good chance that he is. He was a fine dog, wasn’t he?” this callous clod makes fun of the child, even calls him stupid. Typical of arrogant religionists, whether Roman Catholic or other, Father Crifasi knows precisely who is and who isn’t in Paradise. His priestly theology holds the keys of the Kingdom! And since the Bible and church tradition and narrow minded clergy long ago decided that animals have no souls, the answer is a cruel negative, with the implication that even the child’s question is sinful.

Another whoosh! and we’ve slammed out of the roundabout, we’ve jumped in time from the young child’s grief back again to the adult man’s disappointing tour of the St. Petersburg zoo. It’s a brief interlude. The two men see a man with a bear, and Sasha informs the American tourist that he can have his picture taken with it. The bear must look depressed; even Sasha, surely accustomed to animal distress, refers to “the poor bear.” The American declines the photo op.

Back in traffic, this time we wait our turn to enter as the speaker, from his adult point of view, reflects on childhood questions: Who, exactly, qualifies for heaven? The usual, of course: Jesus and his mother, all the famous saints, but then — where do those lesser ones fit in? They have no more right of entry than Spot or any animal soul.

Saint Barsanuphius, born in Egypt — no one knows exactly when — died in 545 A.D. He occupies a niche in the pantheon of saints, and is venerated by both the Roman Catholic and the Greek Orthodox churches. Saint Frideswide, vaguely thought to be the daughter of a minor Anglo-Saxon king and thus a princess, lived from ca. 650-727 A.D. She is less obscure than some in the pantheon, since she is the patron saint of Oxford, both the city and the university. Saint Jutta of Kulmsee, patron saint of Germanic Prussia, lived from ca. 1200-1264 A.D.

We guess that the speaker was well indoctrinated in parochial school, no doubt there were lessons on lady abbesses of Byzantium, on desert anchorites like Simeon Stylites (see Luis Buñuel’s 1965 film Simón del Desierto), and lectures on those priests and monks and holy men of every sort who killed multitudes of New World natives for their refusal to venerate the True Cross.

The speaker is now a sophisticated man of the world. How do we know that? He quotes Leonard Woolf in an incongruous phrase that blends animal rights with political theory. Leonard Woolf (1880-1969) outlived his wife, Virginia, by twenty-eight years.)

“Pets are silly.” This doesn’t sound at all like the speaker. I take it as a fragment of interior monologue, a childhood phrase remembered. Later, as he matured, he realized that a world without animals would be a place where he didn’t want to live. An unlikely segue to Sam Cooke’s 1961 debut album. One of his songs is an up tempo “Ol’ Man River,” from the 1927 Broadway musical Show Boat. Many consider the best rendition of the song the one by Paul Robeson, who sang it in the 1936 film, recorded it in 1938, after which it became his signature song.

The speaker is recalling this line from the song: “I’m tired of living and I’m feared of dying.” (The lyric is often changed to “scared of dying.”)

Next, a wonderful image: Spot, like most young dogs, turned himself “inside out with joy” when the speaker came home from school. This in dramatic contrast with joyless, tight-lipped Father Crifasi and the prison-like atmosphere of the parochial school, where the boys “filed in as slowly as we could” like Russian prisoners in the Gulag.

Another sharp turn and the roundabout we’re now on is no longer an actual one but a great misty circle where the dead, among them the speaker’s parents and departed friends, remind him of statues in one of the Russian cities visited on his trip.

We don’t exit the roundabout. We ascend.

Sun and darkness mix in a strange veil that curtains the future, even though the speaker imagines that “across the river” — not the River Neva that flows through St. Petersburg but the river of time, or the River Styx, which in Greek mythology separates the living from the dead — over there, across the river, life is renewed. Without benefit of clergy, and not a saint in sight.

In a triumphant ending, the speaker imagines that on the other side of that river all the departed animals are waking up — the birds, the zoo animals, and there to welcome him, turning himself inside out with joy, is Spot.

Used with permission of the poet. “Is Spot In Heaven?” appears in David Kirby’s book, “Get Up, Please,” published in 2016 by Louisiana State University Press.

The Poetry Zoo is my online anthology of poetry about animals. It is free to all readers, and will continue to be so. I hope, however, that you will consider making a contribution to PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals). More on PETA in a later post. Donate to PETA

Insightful and entertaining!

Was Eleanor B Campbell the illustrator of Dick and Jane pages?